Starting a fresh .vimrc

Why start a fresh .vimrc?

Starting off, you might ask “Why start a new vim config from scratch”? This is

the part where I ought to tell you something convincing like: “It had been

gathering cruft over the years. It was time to purge and streamline it. Remove

all those long forgotten keybindings and plugins I once set up but never used.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. My .vimrc was epic. It was

a testament to the journey my text editor and myself had been on over the years.

Sure, there were some warts and some cruft. But it would never have occurred to

me to simply remove it and start afresh. Usually, a good re-factor was all it

needed.

Instead, yesterday, in a sleep deprived state, when wanting to delete a symlink

that pointed to my .vimrc, I deleted the original. Yes, that happened. The

instant feeling of dread only got compounded by my realization that it had been

years since I had committed anything to the github repository that kept track of

all my config files.

I suppose I could’ve dove into file recovery and Ext4 journaling, but I decided to make lemonade instead, and start afresh. I figured the only plugins and settings I would remember off the top of my head would be the ones I actually use on a daily basis. Turns out, I use a lot of plugins on a daily basis.

General settings

The following settings simply modify vim’s default behavior to something more sane. The easiest way to get the bulk of these sensible defaults set up would be through Tim Pope’s sensible.vim plugin. Since I add a bunch more, I prefer to forego the plugin and simply keep all my settings in one place.

Tab behavior

set tabstop=2 "Width of a tab

set shiftwidth=2 "Indentation width (using '>' and '<'

set expandtab "Replace tabs with spaces

set softtabstop=2 "Bacspace through expanded tabsMost of these are fairly self-explanatory. I expand spaces to tabs, because Guido says so Also, I write a lot of javascript. Despite Promises finally being part of ES6, callbacks are still a thing, and 4 space indentation eats up screen estate like popcorn.

Sanity and embellishments

set encoding=utf-8

set scrolloff=3 "Scroll when cursor is 3 lines from the screen edge.

set autoindent "Automatically place indents on newlines.

set showmode "Display mode in the bottom line.

set showcmd "Show command that is currently being formed.

set hidden "Abandoned buffers are hidden, rather than unloaded.

set wildmenu "Command completion inside vim command mode.

set wildmode=list:longest

set visualbell

set cursorline "Highlight the line the cursor is on.

set ttyfast "Basically speeds up redrawing. Good for big vimdiffs.

set ruler "Show line and column number at the bottom.

set backspace=indent,eol,start " Backspace through everything

set laststatus=2 "Always show a status line.

set number relativenumber "Show hybrid relative linenumbers.

set undofile "Keep undo history in a file, available after closing.Vim has a tendency to have very undescriptive variable names, so I tend to add

comments documenting what they do when it’s not obvious. If you don’t get what

set encoding=utf-8 does, well, then… carry on doing your thing.

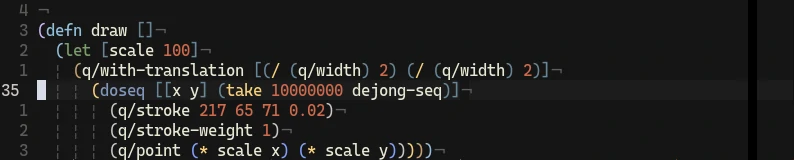

A couple of things to point out. set number relativenumber is amazing. Given

how jumping around in a file by using keyboard commands is 90% of most people’s

work flow, it’s a miracle it took so long for this to become a thing. It looks

like this:

So, vim is a modal editor. It’s claim to fame comes down to the fact that you

can do anything without ever leaving the keyboard. Delete the next three

words?

So, vim is a modal editor. It’s claim to fame comes down to the fact that you

can do anything without ever leaving the keyboard. Delete the next three

words? d3w. Delete an expression inside parentheses and drop into insert mode?

ci(. Comment out the next 14 lines of text? gc14j. And that is where line

numbers become essential. Every text editor has a gutter on the side showing

line numbers. But does anyone really care what number the line 15 lines up is?

Most people only really care about the line they are on. Vim users, especially,

tend to have mixed feelings about absolute line numbers. Suppose I’m on line 334

and I want to delete some lines, starting on that line until line 358. Now all

of a sudden I have to do mental arithmetic just to be able to delete 24 lines

(or is it 25?). Relative line numbers simply tells you the distance of each line

to the one you are on. If I want to delete down to the line that reads ‘14’,

I simply plug that number into my command. Done. Relative line numbers have one

flaw, though. The current line always reads ‘0’, since it is 0 lines away from

the cursor. Pretty redundant, isn’t it? Instead, hybrid line numbers show the

absolute line number for the current line, and relative line numbers for the

rest. Pretty neat.

Another great one is set undofile. Vim keeps track of an undo history is

a separate file, so you can go back to any file, months later, and still have

access to any recent changes you made, without having to go through your git

commit history. Vim’s approach to undoing changes is actually really powerful,

more on that later.

Searching, wrapping, highlighting

set ignorecase "Case insensitive search

set smartcase "All-lowercase = case-insensitive, caps = case-sensitive

set gdefault "Default search and replace commands act globally.

set incsearch "As-you-type search results

set showmatch "Matching bracket is highlighted.

set hlsearch "Highlight all search matches

nnoremap / /\v "Use standard perl/python regexes

vnoremap / /\v "Use standard perl/python regexes

"Text wrapping handling

set wrap

set textwidth=80

set formatoptions=qrn1

set colorcolumn=80

"Show some invisible characters.

set list

set listchars=tab:▸\ ,eol:¬

" Color scheme

syntax on

set background=dark

colorscheme jellybeans

set termguicolorsI tend to prefer the more powerful Perl-like regexes over vim’s. set colorcolumn=80 draws a dark band on column 80, indicating where I should start

a new line. I tend to be a bit capricious when it comes to color schemes, but

for the moment I seem to be pretty happy with jellybeans.

Navigation

"Turn off arrow navigation...

nnoremap <up> <nop>

nnoremap <down> <nop>

nnoremap <left> <nop>

nnoremap <right> <nop>

"Turn off arrow navigation in insert mode as well.

inoremap <up> <nop>

inoremap <down> <nop>

inoremap <left> <nop>

inoremap <right> <nop>

"Moving up and down screen line rather than file line

nnoremap j gj

nnoremap k gk

noremap H ^

noremap L $Ah, the truly controversial one. Most seasoned vim-users will recommend

newcomers to vim to disable the arrow keys. This forces them to spend most of

their time in ‘normal’ mode and use the (far more ergonomic) hjkl navigation

keys. It’s usually called “hard mode”.1 I don’t feel like I really need

this to be enforced anymore, but it’s just such a big part of the vim spirit,

that I decided to leave them in. Another setting of note is the remapping of j

and k to gj and gk respectively. Rather than moving down by a file line

(i.e. separated by a carriage return), j and k will move down by a visual

line. This is especially useful if you have long lines of text that are visually

wrapped (without line breaks), which would make it tedious to navigate.

Key bindings

let mapleader = ","

inoremap # X<BS># "Stop it, hash key.

nnoremap <space> zA<CR> "Map <space> to togge folds:

nnoremap <leader><tab> <C-w><C-w> "Map <leader><tab> to move to next split

nnoremap <space><space> :w<cr> "Use double-<space> to save the file

inoremap jj <Esc> "Remap jj to Esc.

nnoremap <F6> :set paste!<cr> "Toggle paste

tnoremap <Esc> <C-\><C-n> "Escape terminal mode (nvim)

nnoremap <leader><space> :noh<cr> "Remove search highlighting

nnoremap <tab> % "Tab jumps to matching bracket

vnoremap <tab> % "Tab jumps to matching bracket

nnoremap <leader>ev :e ~/.vimrc<CR> "Edit .vimrc

nnoremap <leader>sv :so ~/.vimrc<CR> "Source .vimrcVim by default uses the Escape key to exit insert mode. This is an ergonomic

disaster, and most people tend to remap the (rather useless) Caps Lock key to

serve as an additional Escape key. Others simply remap some unlikely combination

of letters to exit insert mode (in this case, jj). Having double space mapped

to save the current file is also insanely quick.2

Plugins

Ah, the plugins. This is where vim goes from being an immensely powerful text editor to being an immensely powerful IDE. I divided up the plugins I use into three categories: General purpose functionality, language specific plugins, and theming. Throughout the years, I’ve gone from managing my bundles using Pathogen, to Vundle, and have now settled on Plug. It’s cleary becoming the community standard for plugin management.

General purpose plugins

Plug 'scrooloose/nerdtree' "Tree view project navigator

Plug 'tpope/vim-fugitive' "Git wrapper

Plug 'tpope/vim-surround' "Bindings for surrounding things with things

Plug 'tpope/vim-commentary' "Easy commenting

Plug 'junegunn/fzf' "Fuzzy finder

Plug 'junegunn/fzf.vim'

Plug 'easymotion/vim-easymotion' "Quick jump to distant text objects.

Plug 'tpope/vim-eunuch' "FS commands in buffer

Plug 'raimondi/delimitmate' "Auto closing brackets/quotes

Plug 'bling/vim-bufferline' "Display open buffers in command line

Plug 'w0rp/ale' "Linting

Plug 'scrooloose/syntastic' "Syntax highlighting

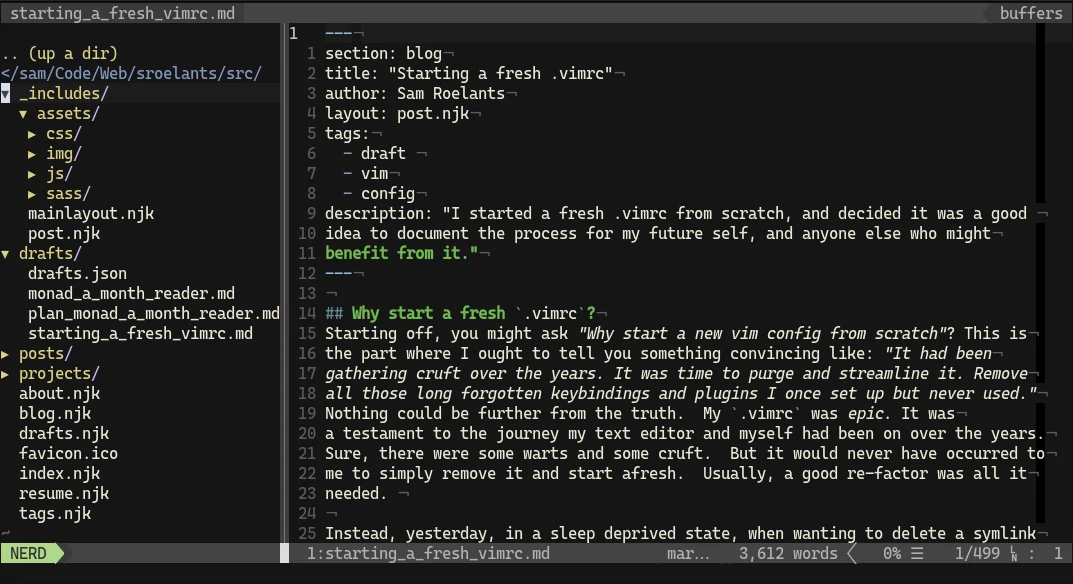

Plug 'shougo/deoplete.nvim' "AutocompleteNERDTree is probably one of the oldest vim plugins out there, if not as old as vim itself. It’s a simple plugin that gives you an on-command side-pane tree navigator of the project you’re working on. It’s a pretty standard feature in any IDE.

I simply have it set to my F1 key to quickly open and close it when needed.

map <F1> :NERDTreeToggle<CR>Fugitive is by far the most effective git workflow I’ve ever used. It allows you to perform all the basic git commands from within vim, but, more importantly, it gives you an increadibly powerful way of vimdiffing changed files with the git index. That’s right, instead of having to interrupt my flow every other minute to make small incremental commits, I can just keep hacking away, and after a while simply selectively diff my file against the index and commit chunks of functionality in separate atomic commits. Fugitive is just one of many incredible contributions to the vim community by the Godfather Tim Pope himself.

Continuing with contributions by Tim Pope,

vim-surround is another one of

those killer features it makes you wonder how it’s not part of the vim core yet.

Vim-surround expands the vim vocabulary by letting you change (cs), add

(ys) and delete (ds) surrounding parentheses, brackets, quotes, HTML tags,

you name it. Changing surrounding double quotes to single quotes becomes Hello

cs"' (change surrounding ” with ’). Deleting a surrounding

<div> is done by dst (delete surrounding tag).

vim-commentary, yes, another tpope

plugin, wires up language-aware commenting with the vim verbs and motions. gcc

comments or uncomments the current line, and more specifically, gc followed by

any vim motion comments the range spanned by the motion. Commenting three lines starting at the cursor is a simple gc3j.

Fzf is a general purpose fuzzy finder (think ‘CtrlP’). It’s lightning fast, and incredibly powerful. It can hook into pretty much anything: the filesystem, git commits, vim buffers. I keep a couple of keybindings handy for the things I use fzf for most.

nnoremap <silent>ff :FZF<cr>

nnoremap <silent>fb :Buffers<cr>vim-easymotion is another

classic. It takes vim motions and turns it up to eleven. Hitting the <leader> key twice, combined with any vim object like a word or paragraph, vim-easymotion overlays labels on every such object, allowing you to instantly jump to the target you need.

vim-eunuch exposes most commonly used

filesystem commands (rm, cp, mv, etc…) from within vim. While vim allows

you to use filesystem commands by prefixing them with a !, these operations

are not in sync with vim’s state. If I delete a file from within vim that I have open in a buffer, I want vim to reflect that change. If I move a file, I want vim to update the location of the file in that buffer. This is precisely what vim-eunuch provides. For example, when removing a file using vim-eunuch, any buffer showing the file is automatically unloaded.

Less high profile, but essential nonetheless are

delimitmate and

vim-bufferline. Delimitmate

automatically adds closing parentheses and quotes while typing. Bufferline shows

a list of open buffers, preventing me from having to :ls every other second

when I’ve forgotten whether I have a file open or not.3

The last couple of plugins are concerned with code quality and ergonomics. It’s

hard to imagine writing any code these days without a linter backing you up.

ALE (short for Asynchronous Linting Engine)

makes use of Neovim’s (and, since v8.0, regular vim’s) asynchronous capabilities

for high speed linting. I have it set up for javascript and python, mostly.

" ALE

let g:ale_linters = {

\ 'javascript': ['eslint'],

\ 'typescript': ['tsserver', 'tslint'],

\ 'python': ['pep8']

\}

let g:ale_fixers = {

\ 'javascript': ['eslint'],

\ 'typescript': ['prettier', 'tslint'],

\ 'sass': ['prettier'],

\ 'html': ['prettier']

\}

let g:ale_fix_on_save = 1Syntax highlighting, another indispensible feature, is provided by Syntastic and autocomplete is done by Deoplete. Deoplete employs the semantics from other language-specific plugins, and comes with a ton of additional completion sources.4

Language specific plugins

These are fairly constant: I want syntax highlighting, linting and sane auto-completion for the main languages I use.

" HTML

Plug 'mattn/emmet-vim'Emmet shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s spent any amount of time typing

HTML. Most editors have an emmet plugin, and if you haven’t used it yet,

I highly recommend it. It simply allows you to type shorthand HTML like

.wrapper>ul.nav>li.nav__item*3 and emmet will expand it into something like

<div class="wrapper">

<ul class="nav">

<li class="nav__item"></li>

<li class="nav__item"></li>

<li class="nav__item"></li>

</ul>

</div>As for Javascript and Python:

" Javascript / JSX / Typescript

Plug 'pangloss/vim-javascript'

Plug 'mxw/vim-jsx'

Plug 'elzr/vim-json'

Plug 'leafgarland/typescript-vim'

Plug 'ianks/vim-tsx'

" Python

Plug 'nvie/vim-flake8'

Plug 'klen/python-mode'Most of these do precisely what you’d expect. Getting correct syntax highlighting and completion for Javascript and all its modern siblings (JSX, typescript, and any permutation thereof), but these plugins seem to work best for me so far.

I’ve recently been getting into Clojure a bit. Most Clojurists will tell you that, if you want the most streamlined development experience you can get, you should use Emacs. Something about Emacs itself being written in in a Lisp making it very suited for REPL integration and so on. I was curious to try it out, and gave Spacemacs a go. Spacemacs is Emacs for vim users. It’s the tightest vim-emulation I’ve yet seen in another editor, and I have to say it had a lot going for it. I ended up going back to vim in the end (I always do), so I was left with finding the best I could get for Clojure development in vim. Thankfully, the situation isn’t nearly as bad as those Emacs evangelists would have us believe!

" Clojure / ClojureScript

Plug 'tpope/vim-fireplace'

Plug 'eraserhd/parinfer-rust', {'do': 'cargo build --release'}

Plug 'guns/vim-sexp'

Plug 'tpope/vim-sexp-mappings-for-regular-people'The pivotal plugin for clojure development in vim is vim-fireplace by, of course, mister Tim Pope. It connects vim to a running repl and allows you to evaluate any code directly in the REPL and have it output either in the command bar, or in a separate scratch buffer. Vim-fireplace also allows for easy documentation lookup and namespace navigation, much like you would do in any other REPL-integrated IDE. So far, I’ve found it a dream to use, and haven’t missed the emacs REPL at all.

Parinfer is another love-it-or-hate-it way of editing clojure. It takes care of (virtually) all of the parenthesis bookkeeping for you, and infers the correct balance by using python-like sensitive whitespace. Seeing as how opinions have always been divided about Python’s use of sensitive whitespace, I expected no less controversy in clojure land.

Some claim it’s like programming with training wheels or crutches. I don’t care. Parinfer makes me fast, and saves me a lot of squinting at parentheses. It worked a lot better for me than paredit, which has a tendency to trap me in a corner, having to jump through hoops to delete a paren it thinks I shouldn’t delete. There are a couple of parinfer plugins for vim, off varying quality. I use the blazing fast plugin written in rust.

The next two plugins that are used in tandem are

vim-sexp and

tpope’s custom mappings. It allows

you to efficiently manipulate s-expressions (think slurping and barfing) using

vim motions and commands. In an expression like (* (+ 1 2) 3 4), you can slurp

the 3 into the sum form by moving the cursor onto the closing paren and

typing >), that is, move the paren left. The plugins also expose a couple of

handy text objects for navigating clojure code (like ‘inner’ and ‘outer forms’)

which, combined with vim-fireplace, make it really easy to send specific forms

to the repl for evaluation.

Look and feel

Some people find theming an unnecessary and frivolous thing. I’m not one of them. I spend a lot of time staring at my editor, I want it to look its best. Also, change being the spice of life, this section is definitely the most susceptible to change. Every now and then, when I’m feeling particularly procrastinatory, I like to mess around with different looks.

Plug 'flazz/vim-colorschemes'

Plug 'vim-airline/vim-airline'

Plug 'vim-airline/vim-airline-themes'

Plug 'junegunn/rainbow_parentheses.vim'

Plug 'Yggdroot/indentLine'

Plug 'junegunn/goyo.vim'

Plug 'junegunn/limelight.vim'vim-colorschemes is a handy collection of a lot of vim color schemes. Who would’ve guessed? As stated above, I’ve currently settled on ‘jellybeans’, it’s been treating me (and my eyes) well.

I used to be a fan of powerline, but I got tired of its bloat and sluggishness. vim-airline is a powerline clone written entirely in vimscript, making it feel much snappier. It comes with a massive pack of themes (I’m particularly fond of ‘bubblegum’). It’s remarkably customizable but, on the whole, I like the default setup just fine. The only feature I added was the tab line at the top of the screen.

" Airline

let g:airline_theme = 'bubblegum'

let g:airline_powerline_fonts = 1

let g:airline#extensions#tabline#enabled = 1

let g:airline#extensions#tabline#left_sep = ' '

let g:airline#extensions#tabline#left_alt_sep = '|'Indentline adds basic indent guides, which is a pretty standard feature you can’t really go without these days. Rainbow-parentheses is a modest tweak, but it pays in dividends. All paired up brackets get their own color, making it really easy to parse a chain of parentheses to get a feeling for the scope of certain expressions. This is particularly handy when I’m writing clojure and parinfer still has me guessing at how expressions should be nested exactly. In fact, I have it set up to be turned on by default whenever I’m writing lisp-like code.

augroup rainbow_lisp

autocmd!

autocmd FileType lisp,clojure,scheme RainbowParentheses

augroup ENDI do all of my writing in vim as well (mostly in markdown files). I’m a big fan of distraction free writing, like you’d find in WriteMonkey or OmmWriter. When I’m writing plain text, I’m not interested in line numbers, other tabs or stats in vim-airline. I’ve found that Goyo combined with limelight gives me a really nice experience.

Limelight takes distraction-free writing one step further by fading out all but the paragraph you’re currently working on. I have it activated by default when I turn on Goyo:

" Goyo + Limelight

autocmd! User GoyoEnter Limelight

autocmd! User GoyoLeave Limelight!

nmap <Leader>l <Plug>(Limelight)

xmap <Leader>l <Plug>(Limelight)Conclusion

Phew. I hope that wasn’t too dry of a sum up of settings and plugins. In the

end, reassembling my .vimrc to a point I was happy with it wasn’t nearly as

hard or painstaking as I thought it would be. (It probably took me longer to

write up this post.) Next up, I’ll have to set up a more streamlined way of

version controlling my config files, so I can avoid this kind of catastrophe in

the future. I hope it was of some use to anyone reading this as well.

Keep on vimming!

Footnotes

-

There are levels of zeal when it comes to “hard mode”. Disabling the arrow keys is only the beginning. Some pros advocate disabling the ability to use any vim motion for more than once or twice in a row. This forces you to learn to use vim’s powerful motions as efficiently as possible. ↩

-

Another benefit of the double space key binding is that, when I do have to use another text editor, I no longer litter the entire file with

:w‘s. I’ve finally lost the muscle memory, and inserting a double space here and there is far less offensive. ↩ -

Fzf, being a fairly recent addition to my plugin list, really helps in that respect as well, allowing me to blindly type fragments of the buffer I want to edit, and fzf opens the buffer straight away. ↩

-

Including a plugin to hook it into TabNine, an ML model that’s trained by going over your code and giving you intelligent completion beyond what any semantic autocompleter could do. I’m really curious to try it out. ↩